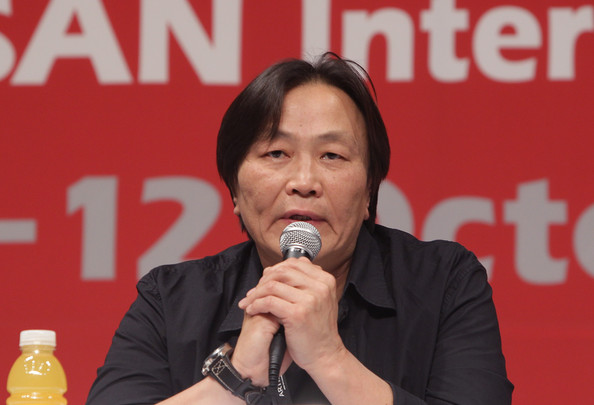

Byamba Sakhya’s Remote Control (2013), played at Dharamshala International Film Festival, 2014. His earlier films include Passion (2010) and Poets of Mongolia (1999).

The central idea of the film seems to be that of control, and therefore of freedom, of liberation. Do you think the film means to somehow use this device (a remote control) to depict a collective, social yearning in Mongolia?

People want more freedom. When I was a child, or a teenager, I only ever wanted to be an adult. But then again, behind this simple story, I am trying to tell you about Mongolia nowadays – the whole society, the whole country is looking for similar freedom. It means we want to control our lives, our future and that’s it.

…Yes, but then it is also about subjective, personal experience, about voyeurism.

It is voyeurism, it is also connected with age, I think. One has to understand that as a country, Mongolia is geographically closed from all sides – so we always want to see more than only our neighbours, so maybe it is also about that kind of voyeurism. But maybe it’s also about the immigrants who come to the city from the small town – they are also looking at this another living style, this overwhelming presence of technology in the city. And they are really curious people; they are always looking for something new, so that constitutes the film as well.

The film is imbued with a very strange, thick rhythm. How did you achieve it? Is there the work of a past director you looked at consciously?

Actually, I had quite a problem with the rhythm of this particular film. Generally, my films tend to be placed very slowly – I just like to provide my audience with a little bit of space, but in this film, I recut it after the first rough cut to make it a little shorter; I cut out thirteen scenes. One of my favourite filmmakers is Tarkovsky, since I studied in Moscow. But I studied cinematography, not direction. My master there was Vadim Yusov, who worked with Tarkovsky for many years – he made four films with him, so I am influenced directly in terms of his use of time.

That’s true. I want to talk about the ending. The main character looks into the camera. He has just participated in an act of destruction, but then he turns towards the camera as if to transfer responsibility.

He asks the audience, ‘I chose this, how about you?’ Think about it – our life is a series of endless choices, and as a result, a series of consequences. We cannot predict each, but there is therefore the influence of Buddhism, which translates into unpredictability. I cannot therefore prepare a clear ending of the film, I tend to end with a question mark. I think it is the end of his dream of control and he begins to face reality, it is when it gets hard for him…

… it begins to get hard also because he is ultimately an outsider in the city.

It is just the economic reality of the situation. It’s reverse now, which is funny. In the countryside, it is getting easier, I mean. It is very hard to setup your life anew in the city, but it is a little bit easier in the countryside. Of course, you will miss certain comforts of civilization, but you can easily live there without any stress.

I also like how you severe the linearity and therefore the reality of his situation to also include fantasy. How did you get the idea for the Flying Monk, for instance?

The story of the Flying Monk is very famous in Mongolia; it is a novel, a classic. But then many people actually believe that it was a real person. Recently, someone actually issued documents that supposedly prove the existence of this monk, who lived and who died, just like a real person. He is an idol, a very famous character – but then ofcourse, young people know a little less about him, but even then, he is not forgotten; they may not know the entire history, but they still know him. He is quite a popular hero. He is in the film because the main theme of the film is, like his story, freedom. You see, in the countryside, access to internet is a little less, but even then, the youngsters in the countryside can read about the Monk in Mongolian literature.

Your previous work has all been documentary. This was the first time you worked with actors, and an actor not close to your age. How was it having another person share the responsibility of the film with you?

It wasn’t very difficult. I was worried about the boy, because he is young and since this is my first fiction film. But most importantly, the actor really liked the story – he found similarity with the character. Usually, I don’t like to tell anyone how to act, I instead like to describe the situations, and help him recall a personal memory from his life from a similar situation, and that’s how we worked.

… Finally, the title, I understand its metaphorical purpose, but it is also ironical since the device isn’t ultimately powerful

.It is provocative, the film is about control. I like simple titles.